Written by Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Jan Hoffman

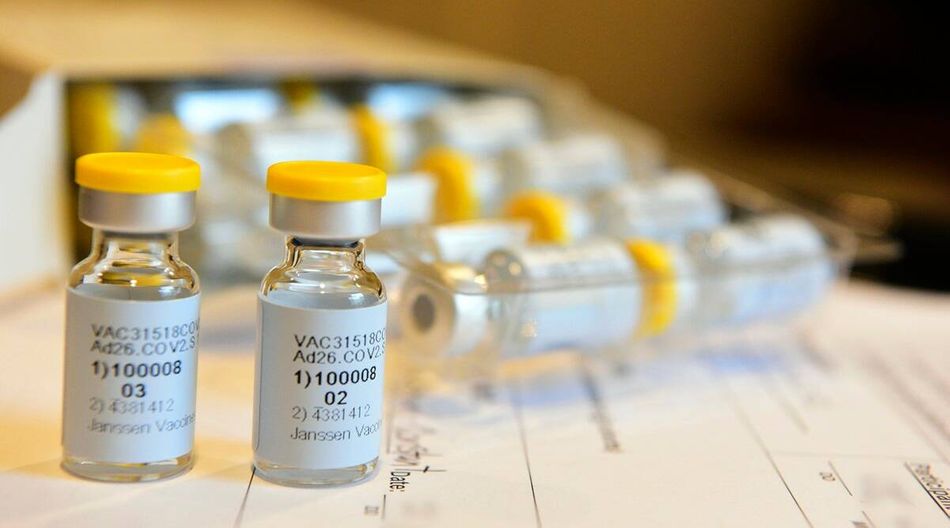

To federal health officials, asking states Tuesday to suspend use of the Johnson & Johnson coronavirus vaccine until they can investigate six extremely rare but troubling cases of blood clots was an obvious and perhaps unavoidable move.

But where scientists saw prudence, public health officials saw a delicate trade-off: The blood clotting so far appears to affect just 1 out of every 1 million people injected with the vaccine, and it is not yet clear if the vaccine is the cause. If highlighting the clotting heightens vaccine hesitancy and bolsters conspiracy theorists, the “pause” in the end could ultimately sicken — and even kill — more people than it saves.

With coronavirus cases spiking in states like Michigan and Minnesota, and worrisome new variants on the horizon, health officials know they are in a race between the virus and the vaccine — and can ill afford any setbacks.

“We are concerned about heightened reservations about the J&J vaccine, but in addition to that, those reservations could spill over into public concerns about other vaccines,” said Dr. Paul Simon, the chief science officer for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Officials at the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday that the break in vaccinations could last only a matter of days as they sort out what happened, determine whether to place limits on the use of the vaccine and examine ways to treat clotting should it occur.

Around the country, people who have taken the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine — and even those who have not — were left to weigh their risks, especially women ages 18 to 48, who accounted for all six cases of blood clots.

The repercussions could be more dramatic than federal officials are bargaining for, just as they were in Europe, where a similar clotting issue has turned the AstraZeneca vaccine into something of a pariah. There, too, officials stressed that blood clotting in people injected with the AstraZeneca vaccine was extremely rare. Yet according to a YouGov poll published last month, 61% of the French, 55% of Germans and 52% of Spaniards consider the AstraZeneca vaccine “unsafe.”

“It’s a messaging nightmare,” said Rachael Piltch-Loeb, an expert in health risk communications at the NYU School of Global Public Health. But officials had no other ethical option, she added. “To ignore it would be to seed the growing sentiment that public health officials are lying to the public.”

The one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine was just beginning to gain traction among doctors and patients after its reputation took a hit from early clinical trials suggesting its protection against the coronavirus was not as strong as competitor vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. Before Tuesday’s pause, some patients were asking for it by name.

“I knew that I wanted to get the Johnson & Johnson — the idea of it being one and done really appealed to me,” said Kayli Balin, 22, a freelance web designer and recent graduate of Wellesley College who was scheduled to get the Johnson & Johnson vaccination Tuesday — only to have her appointment canceled. Now she will get the Moderna vaccine, she said.

But amid the blizzard of news and social media attention around the “pause,” those gains may well be lost, especially if the rare blood clotting feeds politically driven conspiracy theorists and naysayers, who seemed to be losing ground as the rate of vaccinations ramped up.

“This is exactly the wrong situation at the wrong time at the very moment that Republicans are reconsidering their hesitancy,” said Frank Luntz, an American pollster who studies messaging for Republicans, a group that has exhibited high levels of skepticism about the coronavirus vaccines.

Brian Castrucci, an epidemiologist and head of the de Beaumont Foundation, which studies public health attitudes, said: “It’s an easy turn to, ‘If they kept this from us, what else have they kept from us?’ We need to get out in front of this very quickly.”

The problem is getting the public to understand relative risk, said Rupali J. Limaye, who studies public health messaging at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She noted that the potential rate of blood clotting in reaction to the vaccine is much smaller than the blood clotting rate for cigarette smokers and for women who use hormonal contraception, although the types of blood clots differ.

Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist with the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, made that point Tuesday on Twitter, noting the incidence of blood clots among those vaccinated, those taking oral contraceptives and those who have COVID-19.

Patients interviewed Tuesday said the news gave them pause — if not for themselves, then for what it would mean for the nation’s ability to slow the spread of the virus. Jen Osterheldt, 33, of Norwalk, Ohio, who is pregnant and received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine about a month ago, said she would take it again, but worried that others would shun it even if the pause was lifted.

“We could potentially be doing more damage with pulling this than we think,” she said.

Officials are not “pulling” the vaccine. They are simply asking for a timeout, in effect, to figure out how best to use it going forward. But that timeout is causing consternation among those eager to be vaccinated, like Polly Holland, a 23-year-old state worker in Worcester, Massachusetts, who was set to get the Johnson & Johnson vaccine next week after scheduling her appointment on Monday morning.

She had hopes of a vacation to Washington, D.C., and of hugging her 82-year-old grandmother again. But on Tuesday, she received an email notifying her of the pause, and telling her that she would have to wait for the Pfizer vaccine instead.

“I don’t think with the number being as low as it is, that they should completely stop and hold us back from getting to the next step of our lives,” Holland said.

Vaccinators Tuesday were already fielding questions from worried patients.

Maulik Joshi, the president and chief executive of Meritus Health in Hagerstown, Maryland, which has given out 50,000 doses of all three vaccines without any reported major reactions, said he had a simple message to calm patients’ fears: “It’s a great thing that they have paused it, and this is science at work.”

That is the message that public health experts say the Biden administration needs to be communicating, especially to people who are undecided about vaccination — the wait-and-see group. Surveys show that group’s biggest concern is the potential for side effects.

In January, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 39% of unvaccinated people would be less likely to take a vaccine if they learned that some patients had serious allergic reactions to it. At the same time, many Americans do not distinguish among the three vaccines being offered in the United States, which could create confusion and add to vaccine skepticism.

In Europe, the public’s confusion over the AstraZeneca vaccine, which was linked to blood clot problems, was exacerbated for weeks as different countries made different decisions, leading to a drop in confidence in the product as well as the monitoring process. American officials should emphasize swiftness of the response here to shore up the public’s confidence, said Piltch-Loeb of NYU.

“People have valid concerns about side effects and vaccines,” she said. “We can talk through that. It’s a lot harder to counter the broad, emotional sentiment of ‘deep-state government conspiracy.’ So by addressing concerns head on and being transparent, the CDC will get meaningful answers and, hopefully, people will come out on the side of ‘I still want to get the vaccine.’”